Kumamoto is a ‘best of both worlds’ type of city. It’s home to fantastic museums, a huge and recently refurbished castle, and upmarket shopping districts. However, the real heart of the city lies in its backstreets, markets, and independent shops and cafés. Getting to know the smaller, cosier districts of Kumamoto is the best way to feel at home there – even if you’re only on a flying visit. The city’s local government has come to the same conclusion, and is running with the theme of domestic comfort by creating the ‘Kumamoto Memorial Museum Trail.’ The trail is the brainchild of the Kumamoto City Cultural Properties Division (CCPD), and features ten former homes of Kumamoto’s major cultural contributors – including that of Japan’s literary darling, Sо̄seki Natsume.

The CCPD have carefully curated a selection of beautiful period homes, all accessible on foot or by city tram. They’ve also created a paper map that contains beautiful photography, marked with every house on the trail. Unfortunately, no website with the same information exists, but the physical map does at least contain a QR code with the Memorial Trail saved as a Google map. Again, pointless if you can’t get your hands on the paper map – luckily, Japan Journeys has you covered: it’s all here.

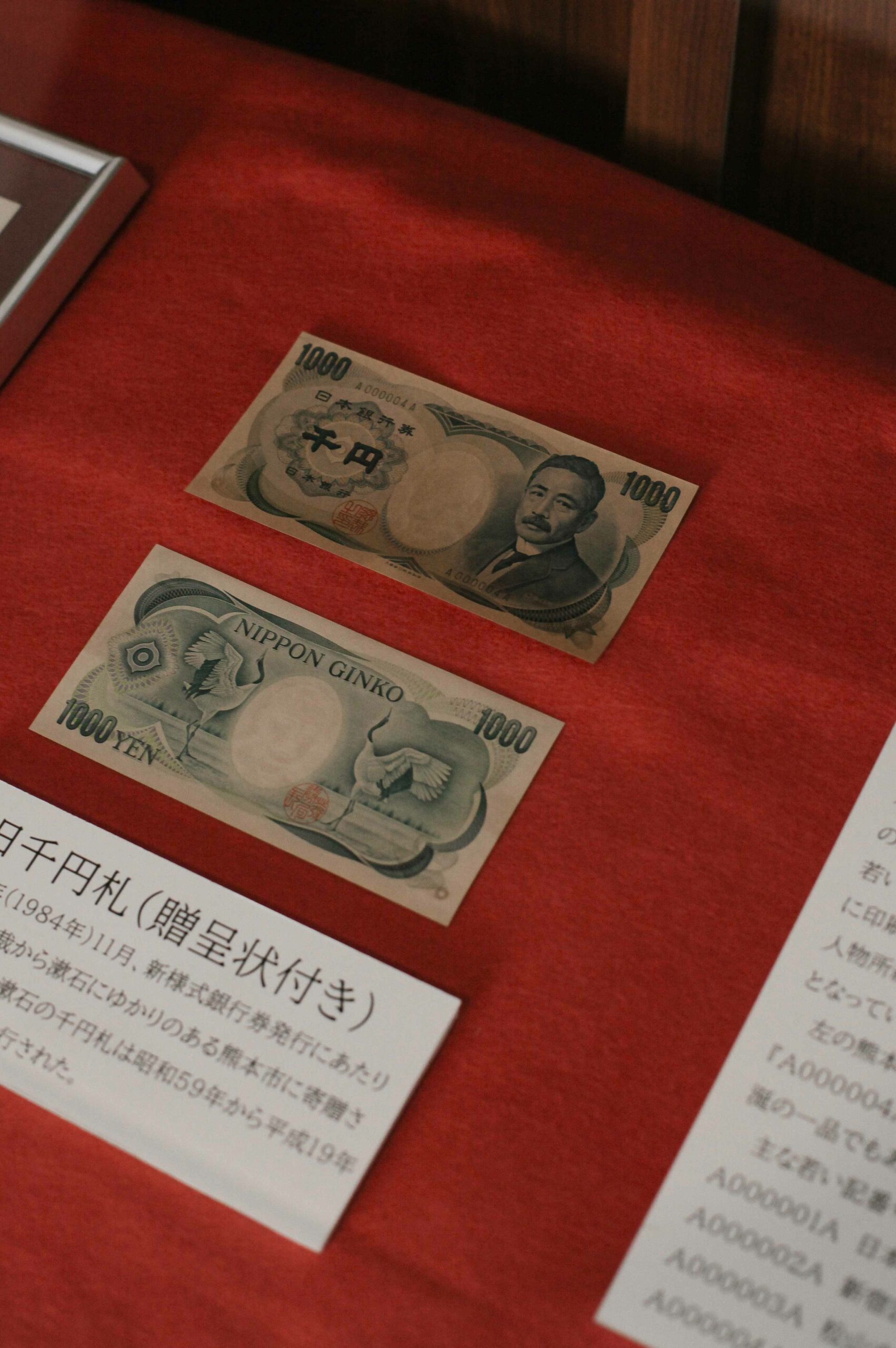

The first stop on the Kumamoto Memorial Trail is ‘Uchitsuboi House’: the former residence of Japan’s most beloved author, Sо̄seki Natsume. You may have already seen his face, as it was printed on the back of all ¥1000 banknotes between 1984 and 2007, with some still in current circulation. Sо̄seki was the author of famous works such as the satirical I am a Cat (1906), Kusamakura (1906), and Kokoro (1914), which is a core text in Japan’s school curriculum even now.

Sо̄seki based many of his works around a theme of loneliness, which offers a direct link to his difficult childhood. As an unplanned child of a mother in her forties and a father in his fifties, Soseki was sent away for adoption as an infant. He was passed around several families until the age of nine, when he returned to his original home. By the age of fifteen, his love of literature was evident, and he informed his family that he wished to pursue writing as a career. He met resistance towards his chosen path; predominantly the disapproval of his father. However, on entering Tokyo Imperial University, Sо̄seki began studying English, reasoning that it would support his future career.

Natsume Sо̄seki was born in 1867; the final year of Japan’s Edо̄ Period. The Meiji period began in 1868, with a dizzying array of social shifts. Suddenly, Japan’s appetite for ‘all things western’ resulted in an explosion of Europhilia. This included the proliferation of city trams and motor cars, western-style dresses and suits, and stylish facial hair (for the men, at least). These cultural shifts occurred predominantly in urban areas; the countryside remained largely unchanged during this time. Sо̄seki’s youth was akin to setting sail on unknown seas, watching all that had represented ‘Japanese-ness’ disappear over the horizon. He quietly resented these changes, as did some of his contemporaries. Fellow author Tanizaki Jun’ichirо̄, born in 1886, wrote an entire book on the topic: the well-known In Praise of Shadows.

While Tanizaki perfected a new blend of semi-facetious whinge-rant, Sо̄seki dwelt more on the realities of the present, rather than a romanticised view of the past. In Kokoro, a young narrator is enamoured with a teacher figure, who although brims with accumulated knowledge, has been inescapably shaped by the past. Called back to his village to visit an ailing father, the narrator finds himself at odds with his home; he is a product of the ‘new Japan’, influenced by rapid social change in urban areas.

How telling, then, that Sо̄seki Natsume’s Kumamoto home has a European façade which is clearly visible from the street, but is Japanese in style throughout, with the exception of a single room. There is even a humble ‘village style’ hut hidden away at the back of the property; built for guests, but perhaps used by Sо̄seki himself.

Like much of Kumamoto city, Sо̄seki’s house was seriously damaged in the 2016 earthquake that struck at a magnitude of 6.5, followed by a second quake of magnitude 7.3. Many of Kumamoto’s attractions (including its crumbling castle) have been closed since this time, only re-opening in 2023. Luckily, Sо̄seki’s former home, (as well as Kumamoto Castle and the home of Lafcadio Hearn) is now fully repaired and open to the public.

There’s a unique kind of thrill in visiting the homes of the deceased. This sounds wildly morbid, but consider this: the desire to poke around the homes of others exists within almost all of us. Modern television has channels scheduled back-to-back with property-based shows in which we’re able to surreptitiously nose around somebody else’s domestic space. Here, though, there’s no harm done; the former owners aren’t going to be offended. It’s a powerful thing to sit in the same room as a great creator; there might be something elemental within their working space that’s waiting to be absorbed. Perhaps, though, it’s enough to look out on the same landscape as they did every day, letting your mind wander in search of connection.

Sо̄seki’s home is beautiful, and it has been lovingly maintained in the years since he departed. The engawa (enclosed veranda) connects his writing room to the property’s rear exit, perfectly framing a simple Japanese-style garden. The outer doors are made from fine wooden frames, holding wavy, pre-industrial panes of glass. As the sun shines into this east-facing room, the shadows of the trees pass through the window panes’ undulating surface, casting a liquid form of light and shadow over the dark wooden floors and tatami mats. It’s still, here, and almost unnaturally quiet. Sit still for long enough, and time seems to slow down, blurred by an interior space that’s been unchanged for over a century.

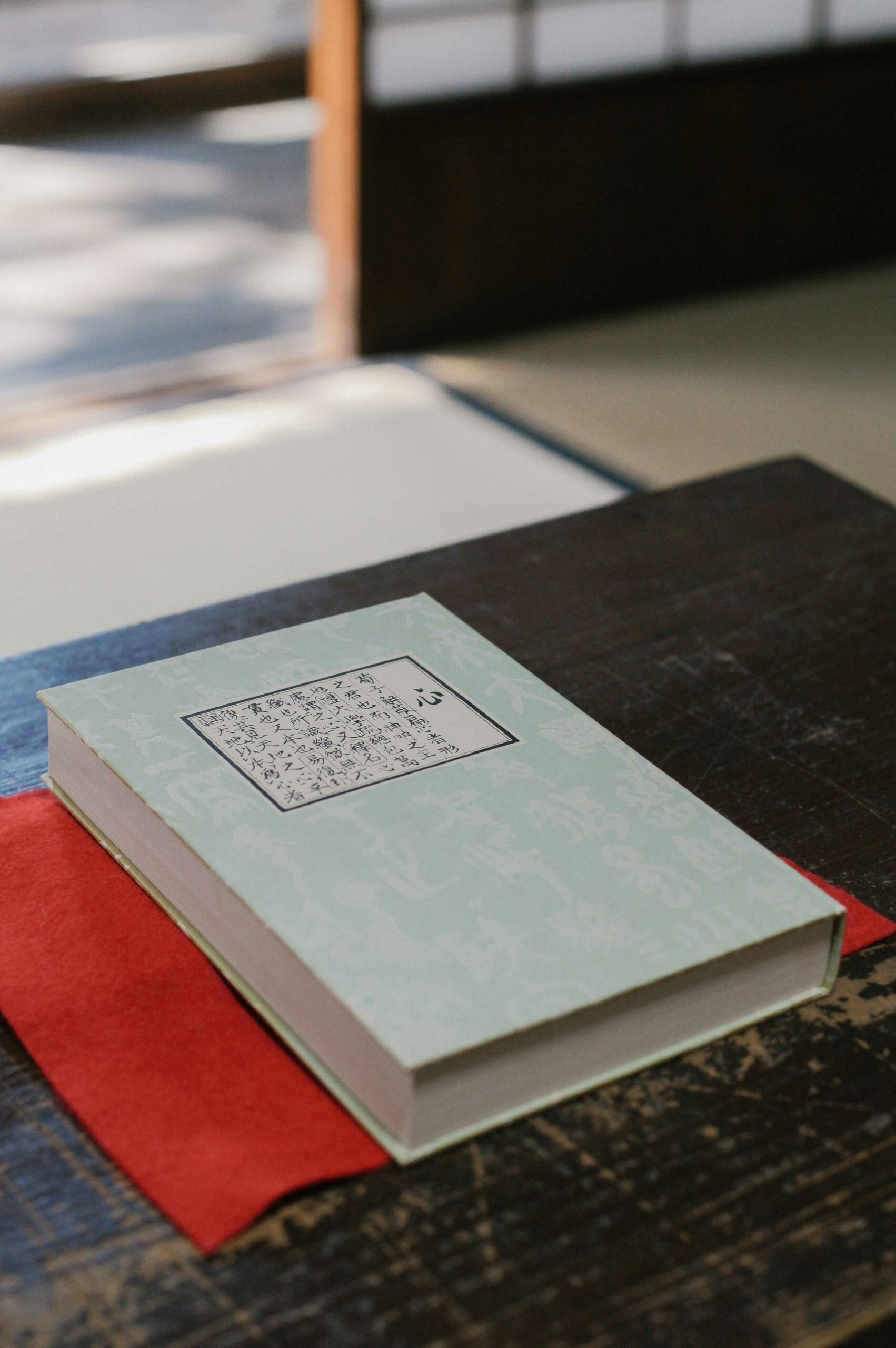

Early in the morning, Sо̄seki’s house is blissfully quiet. It’s a lesser-known attraction in Kumamoto, and it’s often possible to be the only visitor there at the beginning or the end of the day. This leaves you free to breeze over the polished wooden floors of the engawa, or to sit and look into the shifting light of the garden. A collection of first and early editions of Sо̄seki’s books are stored on a small shelf in his writing room; although they’re all in Japanese, the artwork on the covers is masterfully crafted. Venturing further into the property, you’ll find small display cases with more relics of Sо̄seki’s life and works, including his face on previously issued ¥1000 notes.

Of course, a home interior can only keep you entertained for so long. True to Sо̄seki Natsume’s love of cats, the rear garden of the property seems to be home to a colony of them. Are they descendents of Sо̄seki’s own pets, or strays who are looked after by the property’s staff? There’s no way of knowing, but it would surely bring bad luck not to pay a visit to Meow Country.

The cat zone requires a right turn before entering the house, following a dust path past some ornamental pine trees. Watch out for the tiger-striped joro spiders who make their webs between these trees – there are several here, conveniently dangling at face height. The cats take a little while to warm up to visitors, but can likely be enticed with a pocket full of cat biscuits.

If you’d like to snoop around Sо̄seki’s house before visiting in person, there’s a pathway on Google Street View that explores the interior. However, it’s nowhere near as good as experiencing the atmosphere for yourself. Rest assured, also, that Dummy Sо̄seki and The Lump are no longer present within the house.

Access:

From the centrally located JR Kumamoto train station, board the ‘A-Line’ city tram, alighting at the ‘Kumamoto Castle/City Hall’ stop. From here, walk for ten minutes, following this route.

Sо̄seki Natsume’s house is close to many of Kumamoto’s best museums, including the Traditional Crafts Museum (map), Kumamoto Castle and Kumamoto City Museum.

Name: Former Residence of Sо̄seki Natsume / ‘Uchitsuboi House’

Address: 〒860-0077, 4-22 Uchitsuboi-machi, Chuo Ward, Kumamoto City

Open: 9:30am to 4:30pm. Closed on Mondays, national holidays and from December 29 – Jan 3 every year.

Admission: ¥200

Website: https://kumamoto-guide.jp/en/spots/detail/79

Post by Japan Journeys.