Japanese New Year, or shogatsu, is the most important date on the calendar. Though it’s celebrated on December 31st, it is markedly different to the traditions seen throughout much of the world. Swap champagne for soba, midnight kisses for Buddhist bell tolls and hangovers for watching the first sunrise…and you’ll come pretty close. Are there countdown parties and booze cruises? Sure. But the majority of locals choose to celebrate traditionally. So when I received an invitation to ring in the New Year with my friend and her family, I couldn’t wait to see what this entailed.

Japanese New Year Traditions

Once the tinsel comes down on Boxing Day, you’ll start to notice more subtle garlands and decorations adorning homes and businesses everywhere. These straw, pine, bamboo and plum branch ornaments symbolize longevity, sturdiness and prosperity. But not everything surrounding this holiday has such a cool, hidden meaning. Another tradition, the fukubukuro lucky bags, is simply an excuse to celebrate shopping and bargain hunting. As things close down for a few days over the New Year period, workplaces hold bonenkai, or “year forgetting parties”—sort of like the good ol’ office Christmas party. After that, employees head home to be with family for a few days. It’s a time for cleaning and for starting the new year as fresh as fresh can be.

New Year’s Eve

Soba and TV

Over at my friend’s spotless house, the night began with eating Toshikoshi Soba for dinner. Literally translating to “year crossing buckwheat noodles”, this is a tradition that helps to break off the old year and cross into the new one. It’s bad luck to eat them at midnight, so we made sure to get in nice and early.

After dinner, while we were still patting our full bellies, I was introduced to another household tradition: watching “kohaku uta gassen”. This live TV special, also known as the “Red and White song battle”, has aired every New Year’s Eve since the early 50s. In it, popular musical acts are divided into gendered teams to compete for the crowd’s favour. It certainly added a bit of razzle dazzle to the night…even if we didn’t know what was going on.

Hatsumōde

As the midnight hour approached, we made our way to the local Buddhist temple for hatsumōde—the first shrine/temple visit of the year. People can choose to be there on December 31st or come over the next few days. Some popular sites draw millions of visitors in this short span.

As we approached on foot, we could hear the rhythmic chanting and percussion echoing from the belfry and every so often the giant bell (bonshō) was struck. Across Japan, as one year crosses into the next, Buddhist monks ring the temple bell 108 times, once for each of the 108 temptations believed to cause us human suffering. My friend had reserved ahead to ensure we could each take a turn ringing in the new year.

Up close with the monks

We arrived to find a monk chanting before a fire fuelled by old charms and amulets. After warming up a little, we made our way down into a waiting room. Staff were handing out cups of warm amazake, a traditional drink made from fermented rice, and calling out reservation numbers in batches.

Soon enough we were in the elevator, then on the roof, watching the monk we could hear from the street. He was kneeling before a percussion set up, hitting a wooden block and chanting. As we advanced in the queue, we could see the monk manning the bell. He held a smartphone in his hand to accurately time each ring, bowed to each person and gave them a 5 second countdown. I’ve been guilty of ringing these big bells too hard and too soft in the past, so my New Year resolution was not to stuff it up. Luckily I hit it just right and absolved one of the earthly sins.

Before leaving, we bought a new talisman for our New Year wish. In fact, there are plenty of things you can buy for luck or as a gift. It’s customary during hastumōde to buy a fortune (omikuji), and if the luck is bad, you can leave it behind with the others. Heading home, we fortunately didn’t have to worry about missing the last train as they run all night across New Year.

New Year’s Day

Osechi Ryori

As we all prepared for bed, we decided we weren’t going to attempt to catch the first sunrise of the New Year (hatsu-hinode). Instead, we slept in and woke up to enjoy some osechi ryori—a traditional pre-prepared meal consisting of symbolic dishes. Our version consisted of:

- datemaki: sweet rolled omelette mixed with fish paste, symbolising knowledge and culture

- kuri kinton: candied chestnuts and mashed sweet potato, symbolises wealth

- kamaboko: broiled fish cake, symbolising Japan/rising sun

- kuromame: black soybeans, symbolising good health

- zōni, a clear soup with grilled mochi cakes.

Kakizome

After breakfast we were thoroughly schooled in the art of shodōu calligraphy. This tradition literally means “first writing” and was once practiced only by the imperial household. Times have certainly changed; two young kids tried their very best to educate a couple of clueless Australians.

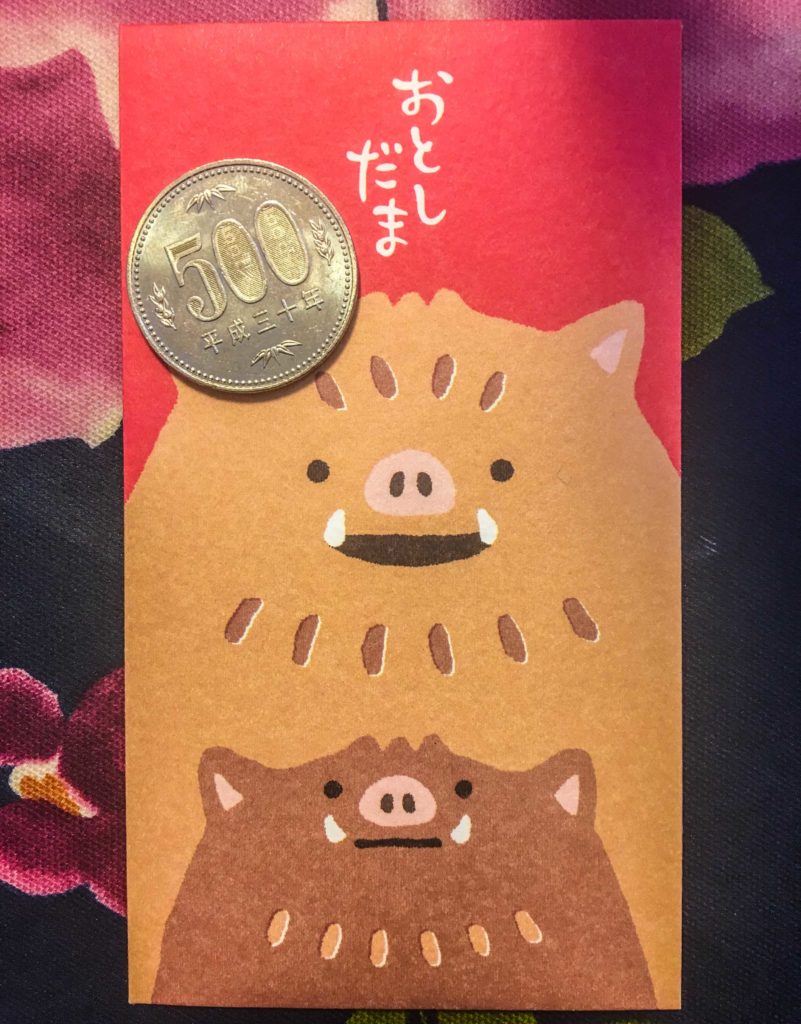

Otoshidama

Though mainly for kids, we got an otoshidama, too! Each year, children receive cute little envelopes of cash from their family, similar to the ‘red packet’ tradition. The envelopes often have a design featuring the Chinese zodiac symbol of the year ahead. In this case, we had a decidedly cute boar.

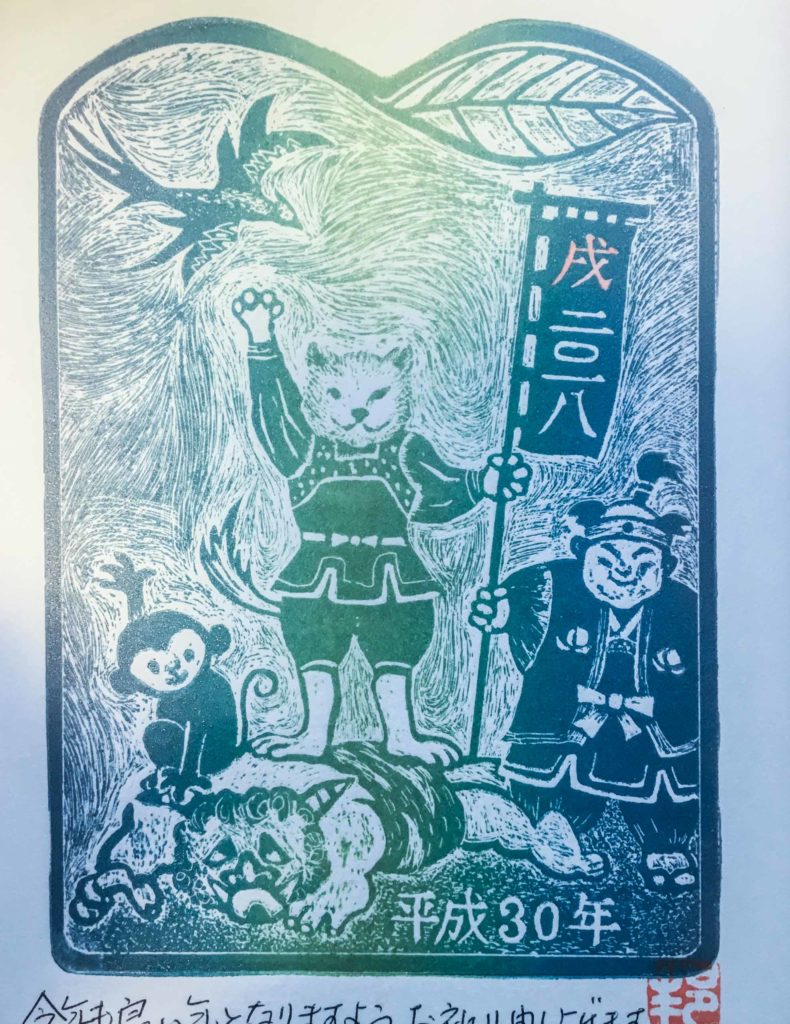

New Year’s Cards

Right around the time we were packing up the calligraphy equipment, the postman made his merry way along the street with another tradition. In Japan, it’s customary to send new year postcards to your friends and family; the postal service holds onto them and delivers them all on January 1st, like some kind of public service Santa Claus. They arrived in a bundle and we went through looking for the best ones. This was my favourite design from a previous year.

For those travelling in Japan around New Year, see if you can make some of these traditions happen for yourself. Reorganise your luggage, find a soba place open for dinner, visit the local shrine at midnight, catch the first sunrise. Some shops and restaurants may be closed for the first few days of January but that’s a great opportunity to slow down yourself. Do as the locals do and set your intentions for a wonderful year ahead.

Post by Japan Journeys.