Japan’s museums are world-class, and it’s no wonder! The island nation is rich in unique plants and animals with active geologies and climatic zones ranging from Yakushima’s rainforest in the south, to Hokkaido’s frozen seas in the north. Culture is abundant and well-documented, the national literacy rate is above 99% (it’s 79% in the USA) and university attendance rates are around 63% (the UK, by comparison, has a rate of 37%). A love of learning is an integral part of Japan’s identity, and a high number of museums is a natural result of this.

Japan’s museums are also varied. From tiny, one-person operations to Ueno’s enormous museum district, there’s a collection of artefacts relating to almost every topic imaginable. Including poo. Natural history museums are also common, and exist in almost every city in Japan. Kagoshima is no exception, and is home to a handful of excellent museums, all conveniently located along one long avenue.

This post will cover two fascinating museums, which are easy to understand in any language: the Kagoshima Prefectural Museum and the Reimeikan Museum.

An easy half-day of museum-hopping would start at the Kagoshima Prefectural Museum, then following the avenue towards the sea, ending at the Reimeikan Museum.

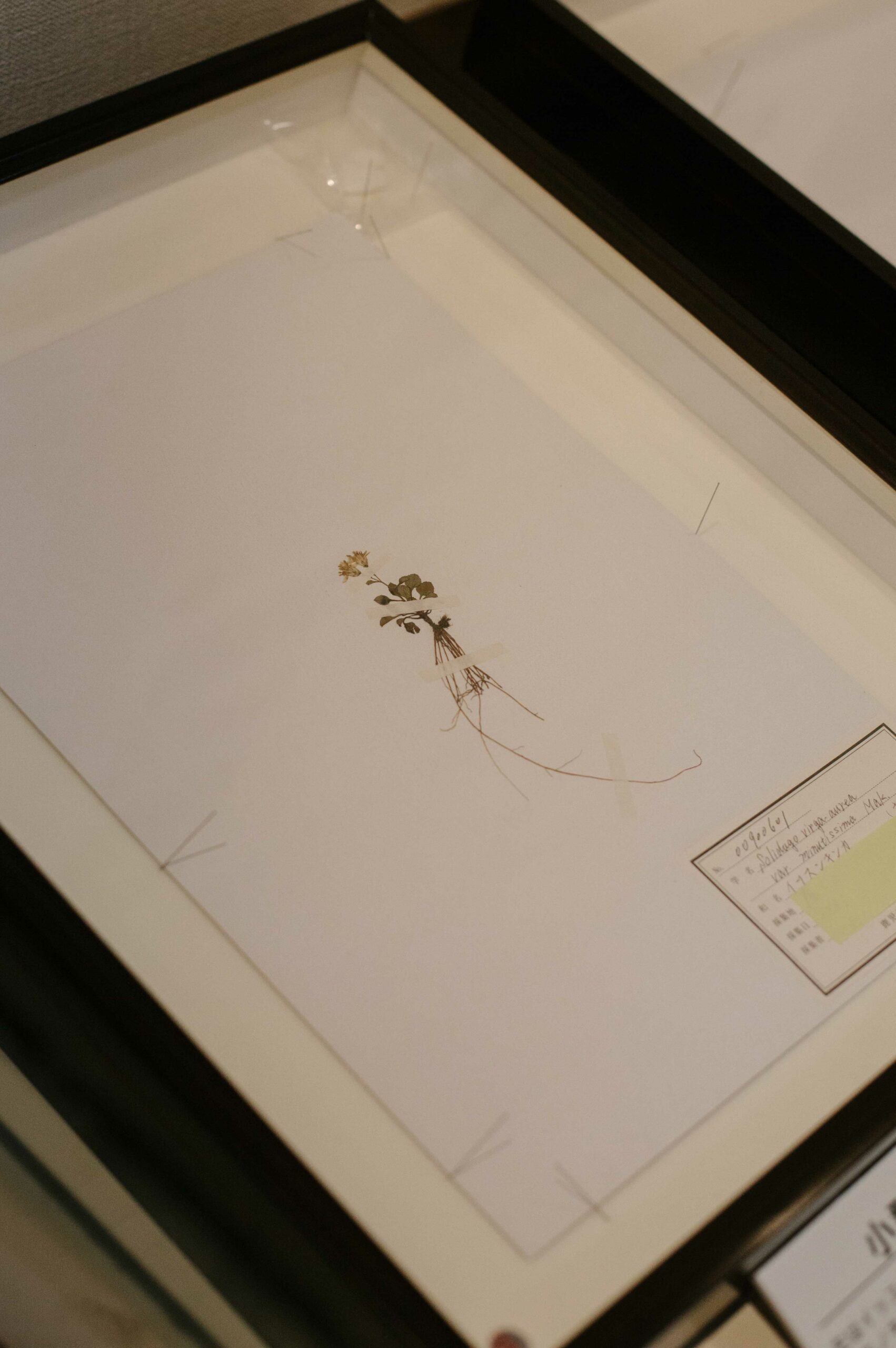

The Kagoshima Prefectural Museum is a family-friendly space, but isn’t limited to children. The exhibitions offer a great introduction to the natural history of Kagoshima, ranging from local animal species to herbaria containing unique local plants, and a collection of geological samples. There’s even a tiny volcano that lights up when you press a button. Boom!

Japan’s municipal museums aren’t grandiose affairs. They’re reminiscent of government schools and city offices; always with restrooms tiled in pink for women and blue for men. There’ll be a metal filing cabinet somewhere, never fully out of sight. Prefectural museums are endearing, because they are earnest. They lack pomp and vanity, and are the result of enthusiastic government employees working to create something they care about, elevating even the most humble offerings. The Kagoshima Prefectural Museum is a wonderful example of such a space. Entry is free, and when entering, you’re asked to choose a plastic tag which best describes you: Japanese, a foreign resident of Japan, or an overseas visitor. Drop your tag into a little bucket next to the front desk – this is the museum’s way of knowing who visits their museum, and helps them allocate resources (for example, more foreign visitors means a bigger need for other languages to be used in exhibits).

On the museum’s ground floor is a corridor lined with fish and insect tanks, and an adjacent room given over to thematic exhibits. 2024 is the 60th anniversary of Yakushima’s designation as a national park, and a small exhibition of the island’s native flora and fauna is displayed in this room.

On the second floor, the museum introduces a wide variety of native animal life, and there’s a ‘hands-on learning’ room which houses herbaria and geological samples (including that little volcano model). It’s here that the sheer variety of animal life in Kagoshima is introduced; everything from raccoons and black bears to insects which would look more at home in the early Carboniferous period. Kagoshima’s geology is also fascinating; the entire region sits atop the Aira Caldera, which is an enormous super-volcano, vented by Sakurajima, whose imposing silhouette towers over Kagoshima city.

The third floor of the museum is perfect for engineering buffs, as it houses exhibits exploring the city’s relationship with geothermal features. Again, as a result of sitting atop a churning mass of pressurised magma, all of southern Kyushu is highly geologically active. Unfortunately, this means regular earthquakes and volcanic eruptions; but also fertile soils and abundant onsen (the boiling city of Beppu is a great example of this).

The top floor of the museum houses a planetarium and mini-cinema, which screens star projections and information films at set intervals throughout the day. They’re all in Japanese, but are atmospheric and enjoyable even if you’re not able to understand them. This floor of the museum is also the most atmospheric; painted black, and lit only with spotlights, it’s home to an impressive range of fossils and plants – a haven for botanists who are interested in Japan’s spectacular native plants. Flora samples are displayed as photographically reproduced pressed plants, and as handmade models, offering a three-dimensional take on their flattened neighbours. Finally, there’s an extensive collection of insect displays, and a small army of taxidermy animals; some of whom look like they’ve had a rough night.

Leaving the museum, head left along the avenue, which is flanked by Meiji and Taishо̄ period buildings, all constructed in variations of a neoclassical European style. The improbable scenes of these buildings, surrounded by date palms, tropical plants and dark, volcanic hillsides disrupts a Eurocentric ‘sense of place.’ However, this blend of tropical flora and slightly out-of-place western grandeur is idiosyncratic to the region, and is something of a ‘signature’ look in Kagoshima, as well as further north in Nagasaki.

In between the Kagoshima Prefectural Museum and Reimeikan are the Kagoshima City Museum of Art, which holds seasonal exhibitions, and the Kagoshima Museum of Modern Literature, which only operates in Japanese, and adjoins the Märchen Fairy Tale Museum, which is an ideal stop for families with small children. The City Museum of Art is a stunning work of architecture, and worth visiting when its feature exhibitions are running. Although the Museum of Modern Literature features zero English-language exhibits, it’s a beautifully designed space, constructed in pale cedar wood and flooded with natural light. The collection of paper ephemera is enough to lure any stationery enthusiast inside.

On, then, to Reimeikan. After the humble Prefectural Museum, the Reimeikan is nothing short of jaw-dropping. Built on the former site of the Satsuma Tsurumaru Castle, the museum rises up behind a traditional castle gate, wrought in wood and iron. Before this is a moat, densely planted with towering Japanese lotus (Nelumbo nucifera), which will be in bloom from July to September. In the palms of the enormous leaves, volcanic ash gathers in drifts. Climbing the steps of the museum; you can see why this happens: Sakurajima, Japan’s most active volcano, rises up from the horizon, towering over the city. The volcano may be in good spirits, puffing out a benign cloud of pale vapour; or it may be churning out thick plumes of volcanic ash. The residents of Kagoshima are prepared for either. However, if you see them running, it’s probably a good idea to follow.

Reimeikan was built in 1983, and offers visitors a ‘journey through time’ as a means of exploring the history and development of Kagoshima. The building’s modern exterior is complemented on one side by a wide reflecting pond, and enormous onigawara (demon tiles) are propped outside its front entrance. The tiles offer a stark contrast between the modern and historical architecture of Kagoshima. Here, as at all of Kagohima’s museums, you can purchase your ticket in English from a digital vending machine. You’re also able to leave whatever you’re carrying in the museum’s coin lockers, before heading inside.

Reimeikan spreads its exhibits over three floors. The first (ground-level) floor focuses on natural history, earliest human settlements, and early agriculture. The second floor moves on to Kagoshima’s middle-history, including its fraught military past as an international port and the forefront of Japan’s dealings with the west. Finally, on the top floor, the recent and contemporary culture of the region is explored through newer types of craft (ceramics, sword-making) and folk histories.

The entrance to the exhibits is illuminated from below by a glass walkway containing a three-dimensional scale model of Kagoshima and the region’s islands. Dioramas of towering trees clinging to volcanic rocks run along one wall, offering an idea of what the pre-human Kagoshima region would have looked like. Extensive examples of Jо̄mо̄n pottery and ritual items are displayed further inside, and a reconstruction of an early Jо̄mо̄n home is placed in the middle of the first hall. The exhibition continues inwards, moving forwards in time to the development of agriculture, the influence of the Ryūkyū islands and Korean peninsula cultures, and the emergence of feudalism under Satsuma clan rulership. Reimeikan’s use of physical artefacts can’t be emphasised enough; the number of exhibits is staggering, and being able to see everything from samurai armour, to temple stoneware, in person and in context, brings the experience to life.

The second and third floors offer a deep-dive into everything from early city planning, to the details of military outfits throughout Kagoshima’s previous seven centuries. Politics and military action in feudal Kagoshima were made more complicated by its role as a ‘frontier’ zone. Trade with Ryūkyū, China, and Korea heavily influenced the internal affairs of the region, including the distribution of wealth and power among warring samurai clans. This was further complicated by the arrival of Portuguese traders in the mid-1500s. Japan’s ongoing contact with these Europeans (notably the Dutch and the Portuguese) would ultimately affect the cities of Kagoshima and Nagasaki more profoundly than anywhere else in the country, especially through the introduction of Western-style firearms and Christianity. This section of the museum will interest any fans of the hit 2004 animé series, Samurai Champloo.

The top level of the museum focuses on ‘post-Meiji’ Kagoshima. It acknowledges both the folk histories and culture of rural Japan, as well as artisanal crafts, such as Satsuma-ware pottery and katana (combat swords) made by the Naminohira smithing line, whose signature katana are unique to the Kagoshima region. There’s even a separate gallery hung with paintings of Kagoshima, made in the European style (by both European and Japanese painters); testament to the exchange of cultures that took place throughout western Kyushu.

The ‘folk culture’ section of the top floor is especially engaging, and is reminiscent of both Osaka’s Museum of Ethnology and Tokyo’s Folk Crafts Museum. It’s a huge collection, spanning multiple rooms, containing agricultural implements, ceremonial items and folk crafts from across the Kagoshima region. Through the museum’s rear window, you’re also able to catch a view of a reconstruction of a traditional Kagoshima-style stone house, which is gradually succumbing to the local plant life.

Thus ends ‘Museum Run Kagoshima’ – it conveniently finishes a few minutes’ walk from the city’s Sakurajima Ferry Port. Ferries depart for Sakurajima island every fifteen minutes, and a return trip only costs ¥200, making it an ideal afternoon option for anyone looking to get up close(ish) to the island’s volcanic crater.

Access: From Kagoshima-chuo (Kagoshima’s central train station), it’s a 25-minute walk along this route to reach the start of the museum trail. If you’re visiting in summer, avoid the heat by taking the city tram or a taxi instead.

Name: Kagoshima Prefectural Museum

Address: 1-1 Shiroyamacho, Kagoshima City, Kagoshima Prefecture

Open: 9:00am – 5:00pm, closed on Mondays.

Admission: Free

Website: https://www.kagoshima-kankou.com/for/attractions/10538

Name: Reimeikan

Address: 7-2 Shiroyama-cho, Kagoshima City, Kagoshima Prefecture

Open: 9:00am – 6:00pm, last admission 5:30pm

Admission: ¥410

Website: https://www.kagoshima-kankou.com/for/attractions/10514

Post by Japan Journeys.