Natural history museums are wonderful places. Where else can you go to view the timescale of the known universe, condensed into a single building? From photons to stegodons, fossils to phosphorescence, much of Earth’s wonderful strangeness can be found on display within a natural history museum. While the Museum of Natural History in London, England, is perhaps the world’s most iconic natural history museum, Tokyo’s National Museum of Nature and Science is a major contender for the title of ‘world’s best.’

As the museum’s name suggests, it isn’t just natural history on display here; there are entire floors dedicated to the history of engineering, and of past, present, and future technologies. Everything technology, from magnetic coil generators to space exploration probes have a home at the National Museum of Nature and Science, with an immense collection spread over six enormous floors.

A visit to Tokyo’s National Museum of Nature and Science offers something for everyone. Its collections are beautifully curated, bridging the gap between science and art with a magnificent array of forms and colours. It’s as suitable for young’uns as it is for adults, with displays and interactive features that expertly achieve ‘kid-friendly’ appeal, without being overly ‘kiddy.’ There’s geology, technology, plants, animals, and all the dinosaurs you could ever dream of, all under one roof.

Located in Ueno, the National Museum of Nature and Science is one of six museums within Ueno park. If you have the stamina, it’s worth visiting a couple in one day, but be sure to factor in a ‘generous’ half-day for the Museum of Nature and Science. There’s so much to see, and every exhibit is as good as the next – you won’t want to skip anything here. Although the museum’s signage is in Japanese, you’ll be able to enjoy everything in English by using the ‘Kahaku’ smartphone app, which can be downloaded at the museum.

The museum is divided into the ‘global gallery’ and the ‘Japan gallery.’ Today’s article focuses solely on the ‘global gallery’ – but be sure to visit the ‘Japan gallery’ too!

You’re free to visit the different floors of the museum in whichever order you like, but there’s also some signage to help people follow the museum’s recommended route. You’ll start in the ‘hall that has it all’ – literally, as this area features an overview of the known universe, from its presumed beginnings to the present day. A circular display sweeps around the perimeter of the hall, displaying relics of deep time in chronological order, starting with meteorite fragments and progressing through to terrestrial minerals, fossilised plants and animals, and man-made items.

There are two panoramic screens, wrapping around half of this circular hall, showing an animation summarising all of known time. It’s beautifully drawn and easy to understand, whether or not you can read the Japanese subtitles. The museum has made the full video available here, if you want to watch it with subtitles auto-generated in your preferred language.

Following the route away from this circular hall, you’re led through a ‘marine zone’, with floor-to-ceiling displays of corals, sea creatures and gigantic samples of preserved seaweed. This connecting zone is a riot of colour, and offers amazing insights into the diversity of the world’s seas and oceans. Following this, you’ll enter the ‘terrestrial life’ zone; an enormous hall focusing on the natural history of contemporary life on the Earth’s surface, and within its oceans. Gaze in amazement at the life-sized model of a sperm whale suspended from the ceiling, and recoil in horror at the sight of a deep-ocean giant squid preserved in formaldehyde.

At the far end of the first floor is the ‘biodiversity zone’ – a kind of natural history velodrome, with towering walls built from resin blocks containing pressed plants, and cabinets with neatly organised specimens wrapping around the remainder of the dome. Life-sized models of fish hang from the ceiling space, adding to the sense of being in a ‘biodiversity fishbowl.’

The next step is to travel from the first (ground) floor, to ‘B1F’, the first basement level. Here, you’ll find all of the reconstructed dinosaur skeletons you could ever hope for! This is the first of the museum’s two ‘evolution of life’ floors, but as the fossil record for dinosaurs is so immense, our extinct friends get a whole floor to themselves. The dinosaur hall is clad in poured concrete, with steel cables supporting dinosaur skeletons to their full height. The layout is reminiscent of the ‘Isla Nublar Laboratory’ scene from the 1993 Spielberg classic, Jurassic Park – an extra dose of natural history nostalgia for the adults. The hall’s exhibits have been carefully positioned to evoke a dynamic scene, with the T-Rex taking pride of place; the only reconstructed T-Rex skeleton to be built in a ‘crouching’ position.

If you’re able to tear yourself away from the spectacular dino hall, your next stop will be the second basement floor, ‘B2F’, where the ‘evolution of life’ selection continues. Here, you’ll find multiple interconnected halls housing sections of the much longer natural history of life on Earth, offering more detail than previous sections of the museum. The first zone introduces single-celled organisms, the earliest known forms of life on Earth. The Proterozoic party zone magnifies our tiny ancestors to give a better understanding of their physical structure, and includes everything from phytoplankton to stromatolites.

We evolve onwards, with interludes of geological samples explaining how the ever-changing surface of the planet is a key driving force in the evolution of life on Earth. Here, the museum’s interior is brought to life with dramatic, sweeping walls of marine fossils, which are illuminated by spotlights, drawing our attention to beautiful examples of trilobites, ammonites and crinoids. There’s even a zone dedicated to fossils from the Carboniferous period, when plants colonised dry land, eventually leaving behind bizarre mineral imprints, and the Earth’s present supply of coal and oil.

Around the corner and into the middle hall of B2F, visitors are met with Earth’s more recent history; the gargantuan mammals of the Paleogene and Neogene periods (roughly 56 million years ago, up until 2.5 million years ago). Humans didn’t exist at this time. We were still resolutely in ape-form, busying ourselves in the treetops and being entirely unproblematic. Without early humans to bother them, land mammals in this time period grew to enormous proportions, examples of which can be seen in this part of the exhibition. The reconstructed skeletons of these megafauna show evolution really taking the ‘throw it all and see what sticks’ approach to animal anatomy. Cue inexplicable chin-teeth, armadillos the size of cars, and sabre-toothed everything.

As evolution stumbles inevitably onward, so visitors are led to the final zone of the B2F exhibition: humans. ‘Mysteriously’ appearing at around the same time as the megafauna ‘vanished’, multiple subspecies of the hominid genus have risen and fallen throughout evolutionary history. The exhibition reconstructs our earliest ancestors (of the ‘hairy, likely to fling poo’ variety), moving through newer iterations of hominid forms, until arriving at the anatomically modern Homo sapiens. Examples along the way include H. neanderthalensis, and the mysterious H. floresiensis, a now-extinct branch of hominids only ever found on the Indonesian island of Flores. H. floresiensis exhibited the remarkable evolutionary feature of ‘island dwarfism’, and stood at around 110cm tall on average. They, too, disappeared from the fossil record shortly after the proliferation of modern humans, around 50,000 years ago.

Perhaps the most arresting feature of the ‘human’ zone of this evolutionary rollercoaster ride is the lifelike model of early Homo sapiens. He’s no tacky waxwork; his hair and facial features are so realistic, you could mistake him for someone sitting extremely still.

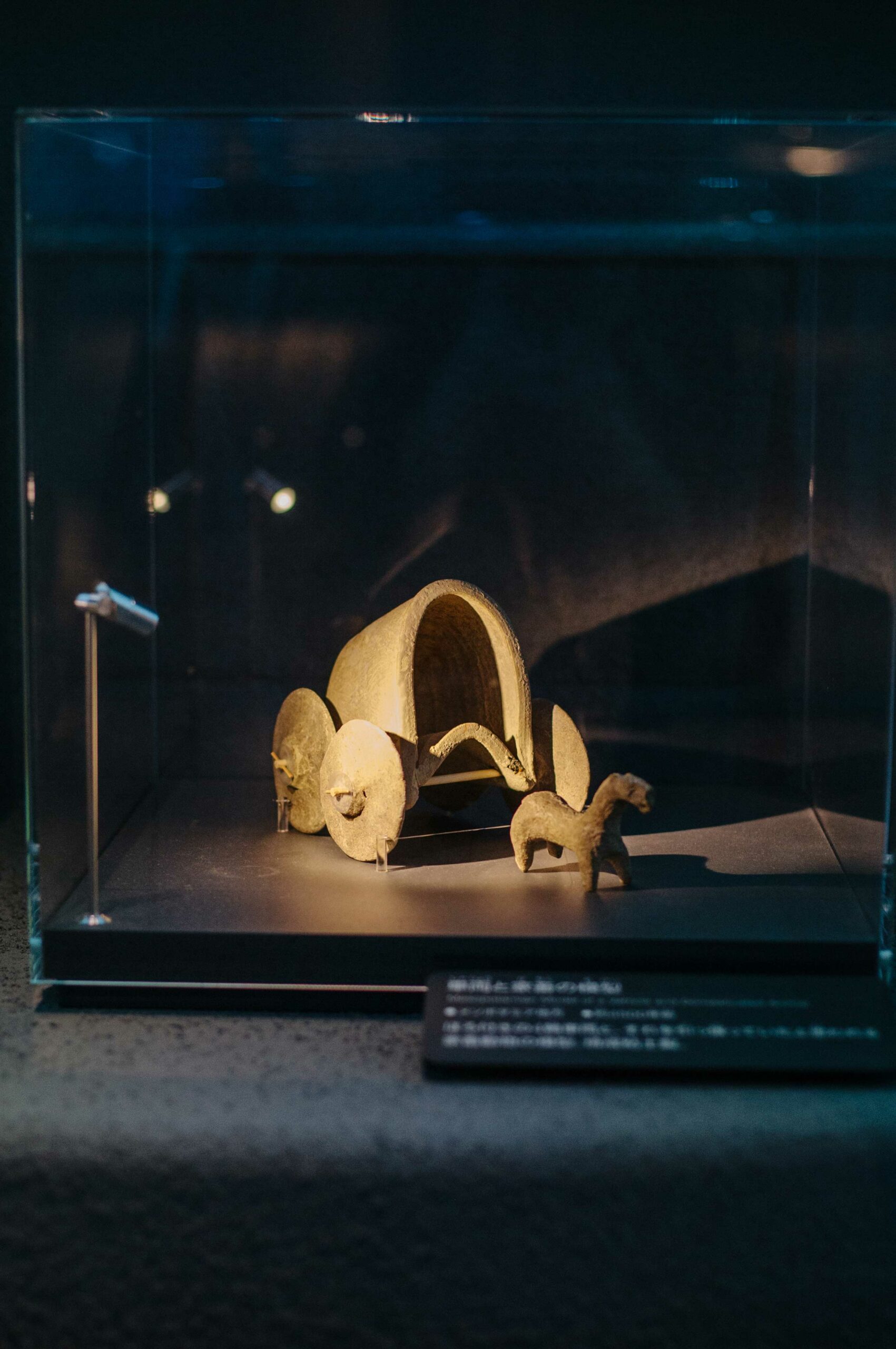

Following the natural progression of human development, the exhibition moves the focus to human-made artefacts, which are perhaps the most defining feature of what makes humans different from non-human animals. We create relics; realisations of thoughts and feelings manifested outside of our bodies, as a form of transmissible idea. A reproduction of several famous man-made relics are displayed here, including the curvaceous Venus of Willendorf and the enchanting, atavistic Lion Man, whose age is estimated at 40,000 years.

After contemplating the nature of humanity, it’s time to head down to the museum’s third basement level, ‘B3F’, which swaps natural history for ‘cosmic philosophy.’ This area is titled ‘Exploring the Structure of Nature’, and offers an in-depth look at the scientific disciplines developed to untangle the mysteries of the universe. Exhibits explore the development of planetary physics, through to particle, theoretical, and quantum physics, before diving into the invisible world of atomic structures, dark matter, and black holes. This part of the museum is a fine example of how ‘hard science’ can quickly become deeply esoteric, and introduces visitors to a physics-led exploration of ‘reality’, before smashing ‘reality as we know it’ into tiny, subatomic pieces.

As you stagger away from the ‘Structure of Nature’ hall, questioning the metaphysics of your very existence, you may be ready to learn about how humans developed the thing we call ‘science’, and how different our ideas of ‘science’ were only a few generations ago.

Returning to the above-ground second floor (2F), you’ll find the ‘Progress in Science and Technology’ hall. As this is Japan’s National Museum of Nature and Science, the exhibition focuses on the development of science and technology in Japan. It features artefacts arranged in chronological order, starting with early understandings of botany, astronomy, and anatomy, and moves on to the development of rugged industrial machinery, before arriving at Japan’s contemporary technologies. These include energy-generating machines, robotics, and space exploration technologies. It’s sure to be a favourite with fans of both modern engineering, and the more whimsical, artistic origins of contemporary sciences.

The final destination is the museum’s third floor, which features a long-term special exhibition focusing on the current features of Earth’s natural history. Titled ‘Animals of the Earth’, the exhibition contains an oval-shaped hall, staggered over many steps and layers. Within walls of glass are preserved mammal specimens, and bird species are mounted in brightly-lit glass cabinets which line the walls. (If you’re not a fan of taxidermy, you may want to give this exhibition a miss). The specimens are, at least, of excellent quality – there are no ‘badly stuffed’ members of this cohort, and the display offers a rare chance to look closely at some of the planet’s more unusual birds and mammals.

Also on the third floor is the ‘ComPaSS’ zone, a parent-child play zone. ComPaSS needs to be booked in advance, as only six people at a time are permitted inside the giant jungle-gym space. It’s a great opportunity for parents to share in learning and exploration with their children through an exciting and dynamic space (and which adult hasn’t secretly wished that they could return to the soft play centres of their youth without being promptly removed from the ball pit?). To book in English, scan the ‘ComPaSS’ QR code on this PDF file with your phone to be taken to the booking portal.

After six floors of adventures in natural history, you may need to sit down and refuel before heading into the museum’s fantastic ‘Japan galleries.’ There is a large restaurant on the mezzanine area of the first floor (1F), and a smaller café selling simple Japanese lunches (onigiri, curry rice) at B1F. If you have any food allergies or refrain from eating certain foods for religious reasons, it’s better to bring your own food with you, as many of the restaurant’s offerings contain gluten, seafood, and other meat derivatives.

Since the pandemic forced many of us to stay home several years ago, the National Museum of Nature and Science embarked on an ambitious project to map every part of the site using photogrammetry, creating a ‘VR museum.’ The end result is spectacular, and if you want to preview the museum before visiting, the link to the VR museum is here. It should be said, though, that nothing even comes close to visiting in person. You won’t regret making time for this amazing place when you visit Tokyo!

The museum’s English language pamphlet offers an excellent overview of what you can see, and is available as a free PDF here.

Access: Travel to Ueno train station, and take the ‘Ueno Park Exit.’ From this exit, follow this route to the National Museum of Nature and Science.

Name: National Museum of Nature and Science

Address: 7-20 Uenokoen, Taito City, Tokyo 110-8718, Japan

Open: 9:00am – 5:00pm (last entry 4:30pm). Closed on Mondays (unless Monday falls on a national holiday, when the museum will instead close on a Tuesday).

Admission: ¥630

Website: https://www.kahaku.go.jp/english/

Post by Japan Journeys.